Library

ACADEMIC/ARCHAEOLOGY/

AMATEUR SLEUTH/COZY/

HUMOR/TRADITIONAL/

SENIOR SLEUTH/TRAVEL/

WHODUNIT MYSTERY

AMATEUR SLEUTH/COZY/

HUMOR/TRADITIONAL/

SENIOR SLEUTH/TRAVEL/

WHODUNIT MYSTERY

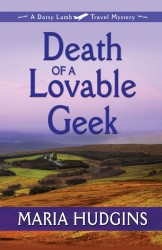

death of a lovable geek

For the life of me, I couldn’t think why a perfectly good Super Bowl ticket

would be lying on the back stairs of a castle in Scotland. But that’s where I

had found one, and I had it in my pocket now, waiting for a lull in the

conversation to bring it up and find out if anyone else knew anything about it.

We, the guests and residents of Castle Dunlaggan, gathered in the library every evening after dinner for coffee, and tonight there were six of us: William Sinclair, our host; Dr. John Sinclair and his wife, Fallon; Tony Marsh; my dear friend, Lettie Osgood; and me, Dotsy Lamb. A wood fire crackled in the fireplace. I sat in an armchair on one side of the hearth, my trip journal in my lap and a small glass of Drambuie on the table beside me.

Lettie, perched in the armchair on the other side of the hearth, studied her road map of Central Scotland and the Highlands as she had done every night since we got here. From my vantage point, Lettie was represented by a few tufts of random-length red hair, two red-nailed hands and a couple of short legs, crossed at the ankles and swinging gently an inch or two above the rug. The rest of her was obscured by several square feet of map.

“Any catastrophes on the road today, Lettie?” Dr. John Sinclair asked, his tumbler of single malt Scotch sloshing as he tacked away from the sideboard. John was the director of the archaeological dig I was lucky enough to be participating in, my college in Virginia having been so kind as to give me a couple of weeks off at the beginning of fall term, but not kind enough to pay for the trip. John was also the brother of William Sinclair, owner of the Castle Dunlaggan at which we were staying.

“One small one,” Lettie said, crunching her map into her lap. “I told the man at the rental place, I said, ‘I can either shift gears or I can drive on the left side of the road, but I can’t do both at the same time. I need an automatic.’ ”

“I’m not surprised that he didn’t have one. We Brits and Scots are keen on shifting our own gears,” John said.

“And putting roundabouts in all the intersections, so you have to go backward around your own elbow to make a turn,” Lettie added.

Fallon Sinclair, John’s wife, scanned the floor-to-ceiling books along one wall and beckoned to Tony Marsh to join her. Tony was John’s second-in-command at the dig and, so far, my favorite of the bunch. He was knowledgeable about Scottish history and about archaeology in general, but not priggish. John Sinclair was just knowledgeable. Fallon pulled out a small book and, eyebrows raised, handed it to Tony.

“Dotsy, here’s the very book for you, compliments of the Sinclair family library.” Tony leaned across a dictionary stand to hand it to me.

A thin volume entitled Macbeth and the Early Scottish Kings, it looked like no more than one evening’s bedtime reading. In the past year I had dug up all the information I could find on Macbeth. The real Macbeth, not the murderous villain invented by Shakespeare. A simple question from one of my students had prompted me to research the Scottish king and discover that little had been written about him compared to all the other Scottish kings. After a few online inquiries, I had concluded that no one in Scotland wanted to talk about him. As soon as I find someone doesn’t want to talk about something, I do.

“Thanks, Tony,” I said, taking the book from him. “Do I have to check it out if I take it to my room?”

Tony and I both turned to the burly, ruddy-faced William Sinclair who seemed confused by my question, but Tony clarified it. “Is this a lending library, William? Does Dotsy need a reader’s ticket?”

“Nae, just take it,” William said.

“Speaking of tickets, can somebody explain this?” I dug into my skirt pocket and drew out a small, rectangular strip. “I found this in the stairwell of the round tower before dinner.”

Tony leaned over the back of my chair and took the strip for a closer look. “Super Bowl?”

“Super Bowl,” I said. “The ultimate American football game. It’s our equivalent of the World Cup finals.”

Fallon Sinclair took the ticket from Tony. “But what you call football isn’t what we call football.”

Lettie said, “What you call football, we call soccer.”

John took the ticket from Fallon. “There’s a diagram of the stadium on the back. Row ten. Section one hundred ten.” He angled the ticket under the beam of a desk lamp. “It looks as if this would seat you near the middle of the field.”

“On the fifty-yard line. I’ve already checked it,” I said.

“How much would a ticket like this sell for?” Tony asked.

“Thousands.”

“Thousands of dollars?” Fallon took the ticket back from John and studied it, almost reverently, I thought. “This may be a memento. Someone’s keepsake, don’t you think? I mean if they paid thousands to attend this game, they wouldn’t simply throw the ticket away.”

Tony turned to William. “Have any of your recent guests been the sort to have attended an American Super Bowl game?”

William took the ticket. “Not that I can recall,” he said.

“Look at the date,” I said. “This isn’t a keepsake. This is a ticket for next February’s Super Bowl.”

William passed the ticket to Lettie. Now, six people: John, Fallon, William, Tony, Lettie, and I, had left our fingerprints on the ticket.

Chapter Two

A half mile from Castle Dunlaggan, Van Nguyen danced in full view of the road. The window of his second-floor room wide open to the wind sweeping in from the moor, he improvised as wildly as the cord to his headphones would allow. A strand of his long black hair escaped from its restraining rubber band, and he smoothed it back with one hand while shifting the mouse connected to one of his computers with his other hand.

One whole wall of the room was stacked solid with electronics. Two monitors flashed a series of photos while two others, with their screen savers morphing from one geometric form to another, stood by. Multiple layers of shirts hung from a peg on the back of the door. Socks, T-shirts, and jeans lay on a shelf above one of the two single beds, intertwined with electric cables, bungee cords, and CDs. Van stopped dancing long enough to click on a few choices from the bank of photos on one of the active screens.

Outside, near the road that ran past, a young woman in an anorak and with a camouflage hat pulled down low over her face watched the window from behind a scrubby Scots pine. She stood on the concrete slab of an old roadside shelter, a remnant of the days when milk in stainless steel cans was picked up by a truck before dawn. Van came to the window, and the girl stepped back a bit, putting more pine between herself and him.

Van plucked an air guitar and tossed his head backward. He sang, a bit off-key, “ ’Cause I got cat class an’ I got cat style!”

His desk light flickered. He pulled his headset off and turned toward the desk. The light flickered again, in unison with the ringing of his cell phone. He yanked the phone from its cradle and said, “Hello.”

A pause, then, “He’s not here.”

After another short interval, Van said, “He’s probably at the camp, hanging out. I guess you’ve already tried his cell phone?”

Then, “Yes, ma’am.”

And a few seconds later, “Maybe he went to the—what do you call it? The loo?—and left his phone outside.”

Then, “Yes, ma’am. I’ll tell him to call you.”

While Van finished his phone call, the girl studied the road in both directions and peered across the meadow toward the Castle Dunlaggan with its dark towers and turrets piercing the night sky. She hitched up her shoulders and walked off, southward, down the road.

* * * * *

Beside a drystone wall some thirty yards from the northwest corner of the Castle Dunlaggan, a blue tarp lay crumpled. Thin fingers of fog crept up the valley, across the field and into its folds as dew collected on its surface.

From under the blue tarp, a laughing horse, a novelty ring tone on a cell phone, whinnied again and again.

We, the guests and residents of Castle Dunlaggan, gathered in the library every evening after dinner for coffee, and tonight there were six of us: William Sinclair, our host; Dr. John Sinclair and his wife, Fallon; Tony Marsh; my dear friend, Lettie Osgood; and me, Dotsy Lamb. A wood fire crackled in the fireplace. I sat in an armchair on one side of the hearth, my trip journal in my lap and a small glass of Drambuie on the table beside me.

Lettie, perched in the armchair on the other side of the hearth, studied her road map of Central Scotland and the Highlands as she had done every night since we got here. From my vantage point, Lettie was represented by a few tufts of random-length red hair, two red-nailed hands and a couple of short legs, crossed at the ankles and swinging gently an inch or two above the rug. The rest of her was obscured by several square feet of map.

“Any catastrophes on the road today, Lettie?” Dr. John Sinclair asked, his tumbler of single malt Scotch sloshing as he tacked away from the sideboard. John was the director of the archaeological dig I was lucky enough to be participating in, my college in Virginia having been so kind as to give me a couple of weeks off at the beginning of fall term, but not kind enough to pay for the trip. John was also the brother of William Sinclair, owner of the Castle Dunlaggan at which we were staying.

“One small one,” Lettie said, crunching her map into her lap. “I told the man at the rental place, I said, ‘I can either shift gears or I can drive on the left side of the road, but I can’t do both at the same time. I need an automatic.’ ”

“I’m not surprised that he didn’t have one. We Brits and Scots are keen on shifting our own gears,” John said.

“And putting roundabouts in all the intersections, so you have to go backward around your own elbow to make a turn,” Lettie added.

Fallon Sinclair, John’s wife, scanned the floor-to-ceiling books along one wall and beckoned to Tony Marsh to join her. Tony was John’s second-in-command at the dig and, so far, my favorite of the bunch. He was knowledgeable about Scottish history and about archaeology in general, but not priggish. John Sinclair was just knowledgeable. Fallon pulled out a small book and, eyebrows raised, handed it to Tony.

“Dotsy, here’s the very book for you, compliments of the Sinclair family library.” Tony leaned across a dictionary stand to hand it to me.

A thin volume entitled Macbeth and the Early Scottish Kings, it looked like no more than one evening’s bedtime reading. In the past year I had dug up all the information I could find on Macbeth. The real Macbeth, not the murderous villain invented by Shakespeare. A simple question from one of my students had prompted me to research the Scottish king and discover that little had been written about him compared to all the other Scottish kings. After a few online inquiries, I had concluded that no one in Scotland wanted to talk about him. As soon as I find someone doesn’t want to talk about something, I do.

“Thanks, Tony,” I said, taking the book from him. “Do I have to check it out if I take it to my room?”

Tony and I both turned to the burly, ruddy-faced William Sinclair who seemed confused by my question, but Tony clarified it. “Is this a lending library, William? Does Dotsy need a reader’s ticket?”

“Nae, just take it,” William said.

“Speaking of tickets, can somebody explain this?” I dug into my skirt pocket and drew out a small, rectangular strip. “I found this in the stairwell of the round tower before dinner.”

Tony leaned over the back of my chair and took the strip for a closer look. “Super Bowl?”

“Super Bowl,” I said. “The ultimate American football game. It’s our equivalent of the World Cup finals.”

Fallon Sinclair took the ticket from Tony. “But what you call football isn’t what we call football.”

Lettie said, “What you call football, we call soccer.”

John took the ticket from Fallon. “There’s a diagram of the stadium on the back. Row ten. Section one hundred ten.” He angled the ticket under the beam of a desk lamp. “It looks as if this would seat you near the middle of the field.”

“On the fifty-yard line. I’ve already checked it,” I said.

“How much would a ticket like this sell for?” Tony asked.

“Thousands.”

“Thousands of dollars?” Fallon took the ticket back from John and studied it, almost reverently, I thought. “This may be a memento. Someone’s keepsake, don’t you think? I mean if they paid thousands to attend this game, they wouldn’t simply throw the ticket away.”

Tony turned to William. “Have any of your recent guests been the sort to have attended an American Super Bowl game?”

William took the ticket. “Not that I can recall,” he said.

“Look at the date,” I said. “This isn’t a keepsake. This is a ticket for next February’s Super Bowl.”

William passed the ticket to Lettie. Now, six people: John, Fallon, William, Tony, Lettie, and I, had left our fingerprints on the ticket.

A half mile from Castle Dunlaggan, Van Nguyen danced in full view of the road. The window of his second-floor room wide open to the wind sweeping in from the moor, he improvised as wildly as the cord to his headphones would allow. A strand of his long black hair escaped from its restraining rubber band, and he smoothed it back with one hand while shifting the mouse connected to one of his computers with his other hand.

One whole wall of the room was stacked solid with electronics. Two monitors flashed a series of photos while two others, with their screen savers morphing from one geometric form to another, stood by. Multiple layers of shirts hung from a peg on the back of the door. Socks, T-shirts, and jeans lay on a shelf above one of the two single beds, intertwined with electric cables, bungee cords, and CDs. Van stopped dancing long enough to click on a few choices from the bank of photos on one of the active screens.

Outside, near the road that ran past, a young woman in an anorak and with a camouflage hat pulled down low over her face watched the window from behind a scrubby Scots pine. She stood on the concrete slab of an old roadside shelter, a remnant of the days when milk in stainless steel cans was picked up by a truck before dawn. Van came to the window, and the girl stepped back a bit, putting more pine between herself and him.

Van plucked an air guitar and tossed his head backward. He sang, a bit off-key, “ ’Cause I got cat class an’ I got cat style!”

His desk light flickered. He pulled his headset off and turned toward the desk. The light flickered again, in unison with the ringing of his cell phone. He yanked the phone from its cradle and said, “Hello.”

A pause, then, “He’s not here.”

After another short interval, Van said, “He’s probably at the camp, hanging out. I guess you’ve already tried his cell phone?”

Then, “Yes, ma’am.”

And a few seconds later, “Maybe he went to the—what do you call it? The loo?—and left his phone outside.”

Then, “Yes, ma’am. I’ll tell him to call you.”

While Van finished his phone call, the girl studied the road in both directions and peered across the meadow toward the Castle Dunlaggan with its dark towers and turrets piercing the night sky. She hitched up her shoulders and walked off, southward, down the road.

Beside a drystone wall some thirty yards from the northwest corner of the Castle Dunlaggan, a blue tarp lay crumpled. Thin fingers of fog crept up the valley, across the field and into its folds as dew collected on its surface.

From under the blue tarp, a laughing horse, a novelty ring tone on a cell phone, whinnied again and again.