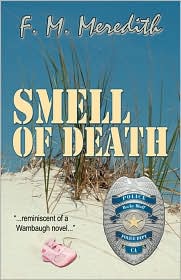

Library

CRIME/ROMANTIC/

POLICE PROCEDURAL/

SMALL TOWN/SUSPENSE MYSTERY

POLICE PROCEDURAL/

SMALL TOWN/SUSPENSE MYSTERY

sMELL OF DEATH

WHEN

RESPONDING TO a suspicious circumstance call, Officer Stacey

Wilbur was met on the sidewalk by the reporting party, an

elderly woman identified as Mrs. Lindhall. Stacey slid from the

seat of her police unit and, as she stood, tucked a wisp of

honey blonde hair into the barrette that held the remainder of

her locks in a neat loop at the nape of her neck.

Mrs. Lindhall towered above Stacey’s five-foot-four inches as she joined the policewoman on the smallsquare of Bermuda grass in front of a tiny stucco

cottage.

“You’re the one who called?” Stacey tried not to notice the critical glance the woman gave her over the steel-framed spectacles perched halfway down a patrician nose. It was an all-too-familiar expression to Stacey. Her slight, slim figure and fine features gave her a deceptively delicate appearance, not matching most of the small, southernCalifornia beach community’s citizens’ ideas

of how a law enforcement officer should look.

Despite the glance and an almost imperceptible sniff, Mrs. Lindhall had the good manners to keep her opinion to herself. “Yes…ah…Officer, I am. You see, I’m most concerned about my neighbor, Darlene Brantley. She has two small children, you see. She’s usually off to work by now. I always see her pass when she takes the children down the street to the sitter. She might be ill, of course, but I tried to reach her by phone. I’ve knocked, but I can’t seem to raise anyone.”

Thank God for all the old people in the country who had nothing more demanding to do than keep track of the comings and goings of their neighbors. “Okay, Mrs. Lindhall, I’ll see what I can find out.”

With a surprisingly agile step, the woman led Stacey to the front door. A pale beige, it had been stained by numerous dirty handprints, big and little. First, Stacey rang the bell then, with her knuckles, rapped sharply against the peeling paint. A strange sound came from inside, a kind of mewing – a kitten perhaps, or a small child. “Good Lord, that’s a baby!”

Stacey grabbed the knob, preparing to use force, but it turned easily. Warily, she pushed the door open and squinted into the dim interior. No matter how often she came upon the scene of a murder, she knew she would never get used to it – not the sight of a corpse, nor the terrible smell of death and blood. This time was no different.

“What is that dreadful odor?” Mrs. Lindhall coughed, crowding through the door behind Stacey.

“Don’t come any further, Mrs. Lindhall,” Stacey ordered. But the woman didn’t listen. Before Stacey could prevent it, the elderly woman had switched on the light.

A ceramic table lamp came on and illuminated the morbid scene. An infant in a bassinet was responsible for the mewing. A boy of around three crouched on the floor, dark eyes big with fear as he stared at the intruders. Tears began when he recognized his neighbor. Scrambling to his feet, he hurled himself at the woman’s knees.

The body of a young woman, clothed only in a man’s tee shirt bunched around her chest, was on the floor, crowded into the space between the couch and coffee table. That she’d either slid or fallen from the couch was evidenced by the bloody slipcover pulled from the furniture and caught under her body.

“I was afraid of something like this. Is she dead?” Mrs. Lindhall asked.

“Yes.” There was no need for Stacey to feel for a pulse. The body had expelled its wastes and blood was clotted around the wounds on the chest, shoulders, and arms.

The baby’s crying grew louder, and Stacey stepped beside the bassinet. By rights, she shouldn’t touch anything, but she couldn’t leave the baby inside the house with its dead mother. She lifted the infant, along with its blanket, into her arms. “There, there little one,” she cooed, patting its back. The baby shivered and settled its head against Stacey’s neck. She could feel its downy hair against her cheek and smell its sweet breath.

Mrs. Lindhall, carrying the boy, scurried out of the house ahead of her. After settling the infant on the front seat of her police unit, Stacey radioed in her gruesome discovery. When the detectives arrived, they would ask her questions, perhaps even send her out to interview the neighbors, but after she wrote her report about the initial discovery of the body, the murder investigation would be out of her hands.

As Stacey had expected, when Detective Milligan arrived, he sent her to knock on doors and question the neighbors. The children had been put in the care of Mrs. Lindhall until the murder victim’s relatives could be notified. Stacey didn’t have much luck finding people home in most of the tiny frame-and-stucco houses that had been built in the mid- and late-twenties.

At one house, a wizened, ancient man in a walker had answered her knock and, when asked about Darlene Brantley, he snarled, “I don’t know or care to know any of my neighbors.” He slammed the door in her face.

The corner house at the end of the block, which was much larger than the others, had a chain link fence around the yard. Several laughing preschoolers crawled upon, slid down, or swung on play equipment, pausing to stare at Stacey as she entered through the gate.

A woman on the porch, with a fat toddler astraddle a denim-clad, plump hip, greeted her with a friendly, “Hi.”

Stacey climbed the steps. “Hello, I’m Officer Wilbur, and I’d like to ask you a few questions.”

“Sure, go ahead.” A crease appeared between the wide set eyes of the young woman as she absently pulled a strand of her long, dark hair out of the baby’s fist.

“Are you acquainted with Darlene Brantley?”

The frown deepened. “Something has happened to Darlene, right? I knew it. It isn’t like her not to let me know when she isn’t bringing the kids. So, what is it? Did she have a wreck in that old clunker of hers? The babies – they’re not hurt, I hope.”

Stacey held up a hand for silence. “The children are fine. I hate to be the one to tell you, but Mrs. Brantley has been murdered.”

Mrs. Lindhall towered above Stacey’s five-foot-four inches as she joined the policewoman on the small

“You’re the one who called?” Stacey tried not to notice the critical glance the woman gave her over the steel-framed spectacles perched halfway down a patrician nose. It was an all-too-familiar expression to Stacey. Her slight, slim figure and fine features gave her a deceptively delicate appearance, not matching most of the small, southern

Despite the glance and an almost imperceptible sniff, Mrs. Lindhall had the good manners to keep her opinion to herself. “Yes…ah…Officer, I am. You see, I’m most concerned about my neighbor, Darlene Brantley. She has two small children, you see. She’s usually off to work by now. I always see her pass when she takes the children down the street to the sitter. She might be ill, of course, but I tried to reach her by phone. I’ve knocked, but I can’t seem to raise anyone.”

Thank God for all the old people in the country who had nothing more demanding to do than keep track of the comings and goings of their neighbors. “Okay, Mrs. Lindhall, I’ll see what I can find out.”

With a surprisingly agile step, the woman led Stacey to the front door. A pale beige, it had been stained by numerous dirty handprints, big and little. First, Stacey rang the bell then, with her knuckles, rapped sharply against the peeling paint. A strange sound came from inside, a kind of mewing – a kitten perhaps, or a small child. “Good Lord, that’s a baby!”

Stacey grabbed the knob, preparing to use force, but it turned easily. Warily, she pushed the door open and squinted into the dim interior. No matter how often she came upon the scene of a murder, she knew she would never get used to it – not the sight of a corpse, nor the terrible smell of death and blood. This time was no different.

“What is that dreadful odor?” Mrs. Lindhall coughed, crowding through the door behind Stacey.

“Don’t come any further, Mrs. Lindhall,” Stacey ordered. But the woman didn’t listen. Before Stacey could prevent it, the elderly woman had switched on the light.

A ceramic table lamp came on and illuminated the morbid scene. An infant in a bassinet was responsible for the mewing. A boy of around three crouched on the floor, dark eyes big with fear as he stared at the intruders. Tears began when he recognized his neighbor. Scrambling to his feet, he hurled himself at the woman’s knees.

The body of a young woman, clothed only in a man’s tee shirt bunched around her chest, was on the floor, crowded into the space between the couch and coffee table. That she’d either slid or fallen from the couch was evidenced by the bloody slipcover pulled from the furniture and caught under her body.

“I was afraid of something like this. Is she dead?” Mrs. Lindhall asked.

“Yes.” There was no need for Stacey to feel for a pulse. The body had expelled its wastes and blood was clotted around the wounds on the chest, shoulders, and arms.

The baby’s crying grew louder, and Stacey stepped beside the bassinet. By rights, she shouldn’t touch anything, but she couldn’t leave the baby inside the house with its dead mother. She lifted the infant, along with its blanket, into her arms. “There, there little one,” she cooed, patting its back. The baby shivered and settled its head against Stacey’s neck. She could feel its downy hair against her cheek and smell its sweet breath.

Mrs. Lindhall, carrying the boy, scurried out of the house ahead of her. After settling the infant on the front seat of her police unit, Stacey radioed in her gruesome discovery. When the detectives arrived, they would ask her questions, perhaps even send her out to interview the neighbors, but after she wrote her report about the initial discovery of the body, the murder investigation would be out of her hands.

As Stacey had expected, when Detective Milligan arrived, he sent her to knock on doors and question the neighbors. The children had been put in the care of Mrs. Lindhall until the murder victim’s relatives could be notified. Stacey didn’t have much luck finding people home in most of the tiny frame-and-stucco houses that had been built in the mid- and late-twenties.

At one house, a wizened, ancient man in a walker had answered her knock and, when asked about Darlene Brantley, he snarled, “I don’t know or care to know any of my neighbors.” He slammed the door in her face.

The corner house at the end of the block, which was much larger than the others, had a chain link fence around the yard. Several laughing preschoolers crawled upon, slid down, or swung on play equipment, pausing to stare at Stacey as she entered through the gate.

A woman on the porch, with a fat toddler astraddle a denim-clad, plump hip, greeted her with a friendly, “Hi.”

Stacey climbed the steps. “Hello, I’m Officer Wilbur, and I’d like to ask you a few questions.”

“Sure, go ahead.” A crease appeared between the wide set eyes of the young woman as she absently pulled a strand of her long, dark hair out of the baby’s fist.

“Are you acquainted with Darlene Brantley?”

The frown deepened. “Something has happened to Darlene, right? I knew it. It isn’t like her not to let me know when she isn’t bringing the kids. So, what is it? Did she have a wreck in that old clunker of hers? The babies – they’re not hurt, I hope.”

Stacey held up a hand for silence. “The children are fine. I hate to be the one to tell you, but Mrs. Brantley has been murdered.”