Bookstore

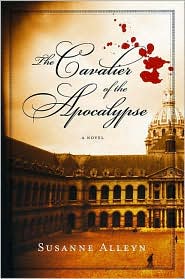

POLICE PROCEDURAL MYSTERY

The Cavalier of the Apocalypse is a prequel in the Aristide Ravel historical mystery series. This book deals with a murder, seemingly with a link to the Freemasons, in 1876 in France. Aristide is a poor writer and he begins to help a policeman investigate the murder. Unfortunately, only that policeman believes Aristide is not connected to the murder so he needs to be careful about what he says and does. There are a lot of twists and turns in this book.

I have not read any of this series before this book. The writing was well developed but this was not a quick read for me. There were a lot of characters and a lot of historical connections that forced me to take my time. I enjoyed the historical aspect of this book. Obviously the author did her research well. I enjoyed the connection to the Freemasons. There were some elements of a French DaVinci Code, but that is not necessarily a bad thing. I would recommend this book to fans of historical mysteries that can handle rich writing.

Melissa A. Palmer

After two mysteries set in the aftermath of the French Revolution, Game of Patience (2006) and A Treasury of Regrets (2007), Alleyn recounts how her series sleuth, Aristide Ravel, became a detective in this superb prequel set in 1786. While visiting the site of a Paris church fire, Ravel, a poor aspiring writer who bears the emotional scars of a long ago family trauma, encounters Inspector Brasseur, whom he recognizes as a former neighbor. Brasseur later seeks Ravel's help when an unidentified man turns up dead in a churchyard, his throat slit and a Masonic symbol carved into his chest, and hires Ravel as a subinspector. As the inquiry continues, Ravel begins to suspect that the Mason may be connected with a plot to replace Louis XVI with the Duc d'Orléans as well as a scandal involving the disappearance of the queen's necklace. Alleyn expertly captures the politics and atmosphere of the period, seamlessly integrating them into a traditional whodunit plot.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

A murder in 1786 Paris turns a hack writer into a first-rate detective.

Aristide Ravel is struggling to make his bread from his writings, most of which criticize the activities of the corrupt church and weak King whose policies will lead to the horrors of the Revolution. In a cemetery, Ravel stumbles upon a murder that he connects to the Masons by the symbols cut into the body. In better times Ravel lived in the same building as police inspector Brasseur, who sees him now as both a suspect and a resource to solve the crime. When Brasseur presses Ravel into working for the police, the clever writer proves his worth by his observations and his connections to the bourgeoisie. Even though the murdered man’s body is stolen from the morgue, his distinctive waistcoat identifies him as one of two missing men: either the Marquis de Beaupréau or Monsieur Lambert Saint-Landry. Lambert’s beautiful wife Eugénie and his sister Sophie cannot imagine who would murder such an earnest man--although like the Marquis, he is a Mason. Ravel and Brasseur pursue the Masonic connection with help from Ravel’s wealthy friend Derville, whose revelation that Ravel’s father was a convicted murderer imperils Ravel’s romance with lively Sophie. Even so, Ravel’s bitterness does not stop him from pursuing the murderer from the lowest hovels to the palaces of the aristocracy.

An intriguing prequel to Ravel’s revolutionary adventures (A Treasury of Regrets, 2007, etc.) with a nice twist in the denouement.

Kirkus Reviews

A series of detective stories tied to the French Revolution? It may sound odd, but Susanne Alleyn makes it work. She’s already written two earlier books (“Game of Patience” and “A Treasury of Regrets”) starring Aristide Ravel as her sleuth. This latest book serves as a prequel, telling the story of the 1786 murder in Paris that first turned Ravel from a writer to a crime solver. The plot brings together everyone from the Masons to the duc d’Orléans, and Francophiles will appreciate the historic detail and rich atmospheric elements that abound.

The Christian Science Monitor