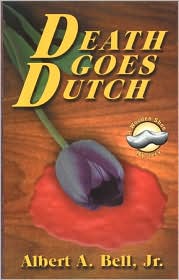

Library

AMATEUR SLEUTH MYSTERY

DEATH GOES DUTCH

How

do I tell a client that his mother is dead?

That question had been gnawing at me all morning. Josh was due in my office in

five minutes and I still didn’t have the answer.

My phone rang. When I answered it the receptionist said, “Ms. DeGraaf, Mr. Adams

is here to see you.”

I grimaced. “Give me two minutes, Joan.”

Josh always showed up on time. I appreciate punctual clients as much as anybody, but today I wouldn’t have minded if he’d been late.

I straightened a few papers on my desk and thought about the ‘staging’ of this interview. My desk faces the wall, with a chair beside it for clients. My framed degrees and social work license hang over the desk. In one corner, where my office opens into a large bay window, I have a sofa, chair and coffee table. That might make a more comfortable setting for what promised to be a painful conversation. In the three years I’d been doing social work at this agency – specializing in helping adoptees find their biological parents – this would be the first time I’d had to tell a client that a birth parent was dead. I had never felt so conflicted about a case.

Or about a client.

I’ve always had a good instinct about people and situations. I’m a Korean-American adoptee myself. I joke that the ‘inscrutable Asian’ part of me senses things. Whatever it is, it kept me from getting in a car when I was seventeen with a bunch of kids who were having too good a time. Three of them

died in an accident a few minutes later. Psychologists say that abandoned kids, like me, have a survival instinct, an ability to know when they can trust somebody or when a situation is safe.

And yet I kept getting mixed signals on Josh.

My conflict with him was summed up by his eyes and his goatee. He has eyes like two pieces of chocolate, the dark kind with the anti-oxidants that are good for your heart. But just below those luscious eyes is that damn goatee. I’ve never known a man whose looks were improved by one of those things.

From our first interview I had wanted to like Josh – not in any romantic sense – but I always felt there was something more I needed to know about him. His answers to my questions didn’t seem evasive, and yet, when I went over my notes later, I found myself somehow . . . dissatisfied.

For instance, in our last session I had asked him what he would say to his biological mother or father when they were reunited. His immediate response was, “I hope you’re rich.” Then he passed it off as a joke. I had to remind myself that he had been a theater major in college and now did freelance advertising and graphics work. Pretence and a glib tongue were the mainstays of his life.

How could I know when to take him seriously?

There was a knock on my partly open door and Josh stuck his head in. “Are you ready for me, Sarah?”

“Yes. Please come in, Josh. It’s nice to see you.”

That wasn’t an idle comment. Josh stood a little over six feet and had thick brown hair to go with those dark eyes.

I slapped myself mentally. I couldn’t be interested in a relationship right now. I still hadn’t gotten over Cal leaving me three months ago. I wasn’t ready to get involved with another man. Certainly not with a client. And not with any man who wore a goatee.

“Let’s sit over here.” I motioned toward the sofa and chair and picked up his file off my desk.

Josh took the sofa, as clients always do. He was wearing an off-white cable knit sweater and brown corduroy slacks that made his eyes appear even a shade darker. He rubbed his hands several times on the upper part of his legs. During several interviews I had come to recognize that as a nervous gesture of his, what psychologists and poker players call a ‘tell’.

I sat in the chair, across from him, with the file folder in my lap. It contained copies of the documents he’d given me – his amended birth certificate, correspondence from the agency to his adoptive parents – and all the information I had unearthed in the last two weeks.

What I didn’t have, though, was his original file from thirty years ago. Nobody in my agency could find it. That worried me. State law requires us to retain all of our paper files relating to adoption cases, and they have to be stored in a secure area. We comply with those regulations, even though we’ve computerized everything, but Josh’s file wasn’t anywhere to be found. I’d had to work from documents he discovered in his adoptive parents’ safe deposit box after their deaths. With my caseload as heavy as it was, I had taken that shortcut. I didn’t have time to turn the place upside down looking for one file.

Josh smiled hopefully. “You said on the phone you had some news for me?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Not good, huh?” His smile faded.

“Well, some good, some bad.”

He leaned back, as if bracing himself for the blow he could see coming and knew he couldn’t avoid, the way I do when the dentist comes at me with that needle full of novocaine. “I can take whatever you’ve got to say. There isn’t a possibility I haven’t imagined.”

I opened the file and studied the first page. Not because I needed to, but because it delayed the inevitable moment when I would have to inflict some pain on him. A lot of pain, actually, and there was no way to deaden it.

“Josh, I don’t know any gentle way to tell you this . . . . Your mother . . . died about five years ago.

That question had been gnawing at me all morning. Josh was due in my office in

five minutes and I still didn’t have the answer.

My phone rang. When I answered it the receptionist said, “Ms. DeGraaf, Mr. Adams

is here to see you.”

I grimaced. “Give me two minutes, Joan.”

Josh always showed up on time. I appreciate punctual clients as much as anybody, but today I wouldn’t have minded if he’d been late.

I straightened a few papers on my desk and thought about the ‘staging’ of this interview. My desk faces the wall, with a chair beside it for clients. My framed degrees and social work license hang over the desk. In one corner, where my office opens into a large bay window, I have a sofa, chair and coffee table. That might make a more comfortable setting for what promised to be a painful conversation. In the three years I’d been doing social work at this agency – specializing in helping adoptees find their biological parents – this would be the first time I’d had to tell a client that a birth parent was dead. I had never felt so conflicted about a case.

Or about a client.

I’ve always had a good instinct about people and situations. I’m a Korean-American adoptee myself. I joke that the ‘inscrutable Asian’ part of me senses things. Whatever it is, it kept me from getting in a car when I was seventeen with a bunch of kids who were having too good a time. Three of them

died in an accident a few minutes later. Psychologists say that abandoned kids, like me, have a survival instinct, an ability to know when they can trust somebody or when a situation is safe.

And yet I kept getting mixed signals on Josh.

My conflict with him was summed up by his eyes and his goatee. He has eyes like two pieces of chocolate, the dark kind with the anti-oxidants that are good for your heart. But just below those luscious eyes is that damn goatee. I’ve never known a man whose looks were improved by one of those things.

From our first interview I had wanted to like Josh – not in any romantic sense – but I always felt there was something more I needed to know about him. His answers to my questions didn’t seem evasive, and yet, when I went over my notes later, I found myself somehow . . . dissatisfied.

For instance, in our last session I had asked him what he would say to his biological mother or father when they were reunited. His immediate response was, “I hope you’re rich.” Then he passed it off as a joke. I had to remind myself that he had been a theater major in college and now did freelance advertising and graphics work. Pretence and a glib tongue were the mainstays of his life.

How could I know when to take him seriously?

There was a knock on my partly open door and Josh stuck his head in. “Are you ready for me, Sarah?”

“Yes. Please come in, Josh. It’s nice to see you.”

That wasn’t an idle comment. Josh stood a little over six feet and had thick brown hair to go with those dark eyes.

I slapped myself mentally. I couldn’t be interested in a relationship right now. I still hadn’t gotten over Cal leaving me three months ago. I wasn’t ready to get involved with another man. Certainly not with a client. And not with any man who wore a goatee.

“Let’s sit over here.” I motioned toward the sofa and chair and picked up his file off my desk.

Josh took the sofa, as clients always do. He was wearing an off-white cable knit sweater and brown corduroy slacks that made his eyes appear even a shade darker. He rubbed his hands several times on the upper part of his legs. During several interviews I had come to recognize that as a nervous gesture of his, what psychologists and poker players call a ‘tell’.

I sat in the chair, across from him, with the file folder in my lap. It contained copies of the documents he’d given me – his amended birth certificate, correspondence from the agency to his adoptive parents – and all the information I had unearthed in the last two weeks.

What I didn’t have, though, was his original file from thirty years ago. Nobody in my agency could find it. That worried me. State law requires us to retain all of our paper files relating to adoption cases, and they have to be stored in a secure area. We comply with those regulations, even though we’ve computerized everything, but Josh’s file wasn’t anywhere to be found. I’d had to work from documents he discovered in his adoptive parents’ safe deposit box after their deaths. With my caseload as heavy as it was, I had taken that shortcut. I didn’t have time to turn the place upside down looking for one file.

Josh smiled hopefully. “You said on the phone you had some news for me?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Not good, huh?” His smile faded.

“Well, some good, some bad.”

He leaned back, as if bracing himself for the blow he could see coming and knew he couldn’t avoid, the way I do when the dentist comes at me with that needle full of novocaine. “I can take whatever you’ve got to say. There isn’t a possibility I haven’t imagined.”

I opened the file and studied the first page. Not because I needed to, but because it delayed the inevitable moment when I would have to inflict some pain on him. A lot of pain, actually, and there was no way to deaden it.

“Josh, I don’t know any gentle way to tell you this . . . . Your mother . . . died about five years ago.