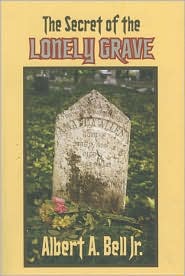

Library

HISTORICAL/YOUNG ADULT MYSTERY

THE SECRET OF THE LONELY GRAVE

The school bus jerked to a stop, the next-to-last stop on the route.

Kendra and I picked up our backpacks. At least I didn’t have to

worry about getting past Dwayne Mitchell this time. Whenever I walk

past Dwayne’s seat, he kicks me or tries to trip me. But today Kendra

and I ran to the bus after school and got seats near the front.

She and I jumped down from the bottom step and the door whooshed shut behind us. When the bus pulled away, Dwayne stuck his head out a window and made an ‘o-o-o-oh’ noise, like a ghost.

“Go soak your head, Dwayne!” I yelled at the bus’s tail lights.

“That was clever, Steve, real clever,” Kendra said. “He can’t hear you now.”

“That’s why I didn’t waste one of my good lines on him.”

She slung her backpack onto her shoulder. “The last time you gave him one of your ‘good lines,’ didn’t he punch your face in?”

I didn’t say anything, just picked up my backpack and started up the road that leads past the cemetery and the church to our homes at the top of the hill. The hill isn’t really steep, but the walk seems longer on a hot day like this.

“I’m sorry,” Kendra said as she caught up with me. “I know Dwayne gives you a hard time. I shouldn’t make it worse.”

“Why does he keep picking on me? I’ve never done anything to him.”

“Dwayne’s just a jerk. School will be out in a week. You won’t have to worry about him this summer.”

“He lives close enough, I bet he’ll be around.”

“Maybe not. Most kids don’t want to hang around here because of the cemetery.”

“Dwayne’s not most kids.”

Dwayne had made that ghost noise because most of our friends consider it scary to walk past a cemetery. But Kendra and I don’t just walk past the cemetery. We walk through it. For me it’s not as scary as walking past Dwayne on the bus. Nobody in the cemetery has ever kicked me.

“Have you finished that story you were writing about him?” Kendra asked. “The one you showed me Saturday.”

“Yeah. I’ll print off a copy and bring it over.”

I like to write stories. Next to baseball, it’s what I like best. In this story Dwayne and I were on opposite teams. I was playing second base, my favorite position. Earlier in the game he had slid into me and cut my hand, but I stayed in the game. Now it was the top of the ninth, a tie game, and the bases were loaded, with two out. Dwayne came to bat. He hit a line drive. I leaped and caught it! Then my team scored in the bottom of the ninth and won the game.

“Are you going to send this one to the newspaper? Everybody liked that story of yours they published on the kids’ page back in March.”

“I don’t think I’ll send this one. Dwayne wouldn’t like it.”

“Who cares what Dwayne thinks? It’s a good story. Just change the names.”

“Yeah, I could do that.”

Like I always do, I looked across the road at the tourist cottages next to Philips’s Grocery Store. My mom and dad owned those cottages before they got divorced, when I was five. They aren’t fancy, just square little buildings set in a U-shape around the office and a swimming pool. Mom tried to brighten them up by painting each door a different color and calling them the ‘Rainbow Cottages.’ The next owner kept the name. They look shabby compared to the new motels that have opened around here recently. But they’re cheaper than the motels.

I wish there was some other way to get to the top of the hill. It’s been six years since the divorce, but every time I look at those cottages I remember my dad teaching me to swim in that pool, or playing ball with me in front of the office.

We were a regular family then. Like the couple sitting by the pool now while their kids played in the water. The father looked up and followed Kendra and me with his eyes.

We get this reaction from strangers a lot. I’ve tried to write a story about it. Some people can’t seem to understand that an African-American girl and a white boy can be friends. We’ve been neighbors for six years and friends for one day less than that.

I forgot about the man when a bulldozer roared farther up the hill.

“Somebody’s starting on another house,” Kendra said.

“Aw, man, that’s the last open lot on this side of the road. I wonder if we’ll ever see the lake again.”

“Maybe some kids our age will move in.” Kendra always thinks things are going to turn out good.

“They’ll probably be friends of Dwayne’s,” I said.

Until last summer we were able to climb down the hill on that side of the road and go swimming in the lake. But then old Mrs. Bradford died. As long as anybody could remember, she lived in a big house at the top of the hill, and she owned all the land down to the ‘Rainbow Cottages.’ Her land had been divided into lots

and sold. Her old house had been for sale since school started. It looked more run-down and spookier every day.

This part of western Kentucky is becoming a popular vacation area. That’s good, my mom says, because it means tourist money coming in. But it also means people like us, who’ve lived around the lake all our lives, are being cut off from it because we can’t afford lake-front property.

Kendra and I walked up the hill in silence. She’s eleven, like me, but tall for her age. I’m four months younger and three inches shorter than she is. At first we played together because there weren’t any other kids our age in the neighborhood. Now we do stuff together just because we like each other. My mom

is assistant manager of a hardware store, so I stay at Kendra’s house, across the street from mine, for the two hours between the end of school and the time my mom gets home.

We usually have a good time, but lately Kendra’s started treating me like a little brother. My mom keeps telling me girls start their growth spurt earlier than boys do. “You’ll catch up with her pretty soon,” she says. That doesn’t make me feel any better, because I know my dad is short, unless he’s taken a growth spurt since the last time I saw him, two years ago.

What really bothers me is that Kendra and I don’t always want to do the same things now. We used to play board games and cards. Now she takes piano lessons and plays tennis. She won the first tournament she played in last month. And she likes to read dumb mystery stories. I like playing baseball, or watching

baseball on TV, or reading and writing about it, and organizing my baseball card collection. I’ve even got some old cards my dad collected when he was a kid.

In the last few months Kendra has also seemed sensitive about being black. During ‘Black History Month’ in school she started reading about famous African-Americans. When we studied slavery and the Civil War in our history class, she got really angry about how the African slaves were treated. She almost cried in class when she presented her report about the Underground Railroad that helped slaves escape.

But she and I still hang out together.

When we’re walking down the hill in the morning and back up in the afternoon we go by her sister’s grave. Her sister died three years ago. She was at a party at another girl’s house and drowned in the swimming pool. Her name was Moniqa and she was six when it happened. Kendra stops by the grave for a minute every morning and every afternoon.

There’s another grave that we look at every day, too. We call it the ‘lonely grave.’ It sits by itself all the way at the lower end of the cemetery, ten yards or so from the other graves and close to a hedge that runs beside the cemetery. It looks pretty old. We’ve never gone over to see who’s buried there, but we always look at it. Sometimes we try to guess why somebody would be buried all alone like that.

Kendra says I ought to write a story about it. But the stories I write always start with something I know, like baseball. How could I write a story about somebody who died—maybe a long time ago—when I don’t know anything about them?

Kendra grabbed my arm. “Steve, look! There are flowers on the lonely grave.

She and I jumped down from the bottom step and the door whooshed shut behind us. When the bus pulled away, Dwayne stuck his head out a window and made an ‘o-o-o-oh’ noise, like a ghost.

“Go soak your head, Dwayne!” I yelled at the bus’s tail lights.

“That was clever, Steve, real clever,” Kendra said. “He can’t hear you now.”

“That’s why I didn’t waste one of my good lines on him.”

She slung her backpack onto her shoulder. “The last time you gave him one of your ‘good lines,’ didn’t he punch your face in?”

I didn’t say anything, just picked up my backpack and started up the road that leads past the cemetery and the church to our homes at the top of the hill. The hill isn’t really steep, but the walk seems longer on a hot day like this.

“I’m sorry,” Kendra said as she caught up with me. “I know Dwayne gives you a hard time. I shouldn’t make it worse.”

“Why does he keep picking on me? I’ve never done anything to him.”

“Dwayne’s just a jerk. School will be out in a week. You won’t have to worry about him this summer.”

“He lives close enough, I bet he’ll be around.”

“Maybe not. Most kids don’t want to hang around here because of the cemetery.”

“Dwayne’s not most kids.”

Dwayne had made that ghost noise because most of our friends consider it scary to walk past a cemetery. But Kendra and I don’t just walk past the cemetery. We walk through it. For me it’s not as scary as walking past Dwayne on the bus. Nobody in the cemetery has ever kicked me.

“Have you finished that story you were writing about him?” Kendra asked. “The one you showed me Saturday.”

“Yeah. I’ll print off a copy and bring it over.”

I like to write stories. Next to baseball, it’s what I like best. In this story Dwayne and I were on opposite teams. I was playing second base, my favorite position. Earlier in the game he had slid into me and cut my hand, but I stayed in the game. Now it was the top of the ninth, a tie game, and the bases were loaded, with two out. Dwayne came to bat. He hit a line drive. I leaped and caught it! Then my team scored in the bottom of the ninth and won the game.

“Are you going to send this one to the newspaper? Everybody liked that story of yours they published on the kids’ page back in March.”

“I don’t think I’ll send this one. Dwayne wouldn’t like it.”

“Who cares what Dwayne thinks? It’s a good story. Just change the names.”

“Yeah, I could do that.”

Like I always do, I looked across the road at the tourist cottages next to Philips’s Grocery Store. My mom and dad owned those cottages before they got divorced, when I was five. They aren’t fancy, just square little buildings set in a U-shape around the office and a swimming pool. Mom tried to brighten them up by painting each door a different color and calling them the ‘Rainbow Cottages.’ The next owner kept the name. They look shabby compared to the new motels that have opened around here recently. But they’re cheaper than the motels.

I wish there was some other way to get to the top of the hill. It’s been six years since the divorce, but every time I look at those cottages I remember my dad teaching me to swim in that pool, or playing ball with me in front of the office.

We were a regular family then. Like the couple sitting by the pool now while their kids played in the water. The father looked up and followed Kendra and me with his eyes.

We get this reaction from strangers a lot. I’ve tried to write a story about it. Some people can’t seem to understand that an African-American girl and a white boy can be friends. We’ve been neighbors for six years and friends for one day less than that.

I forgot about the man when a bulldozer roared farther up the hill.

“Somebody’s starting on another house,” Kendra said.

“Aw, man, that’s the last open lot on this side of the road. I wonder if we’ll ever see the lake again.”

“Maybe some kids our age will move in.” Kendra always thinks things are going to turn out good.

“They’ll probably be friends of Dwayne’s,” I said.

Until last summer we were able to climb down the hill on that side of the road and go swimming in the lake. But then old Mrs. Bradford died. As long as anybody could remember, she lived in a big house at the top of the hill, and she owned all the land down to the ‘Rainbow Cottages.’ Her land had been divided into lots

and sold. Her old house had been for sale since school started. It looked more run-down and spookier every day.

This part of western Kentucky is becoming a popular vacation area. That’s good, my mom says, because it means tourist money coming in. But it also means people like us, who’ve lived around the lake all our lives, are being cut off from it because we can’t afford lake-front property.

Kendra and I walked up the hill in silence. She’s eleven, like me, but tall for her age. I’m four months younger and three inches shorter than she is. At first we played together because there weren’t any other kids our age in the neighborhood. Now we do stuff together just because we like each other. My mom

is assistant manager of a hardware store, so I stay at Kendra’s house, across the street from mine, for the two hours between the end of school and the time my mom gets home.

We usually have a good time, but lately Kendra’s started treating me like a little brother. My mom keeps telling me girls start their growth spurt earlier than boys do. “You’ll catch up with her pretty soon,” she says. That doesn’t make me feel any better, because I know my dad is short, unless he’s taken a growth spurt since the last time I saw him, two years ago.

What really bothers me is that Kendra and I don’t always want to do the same things now. We used to play board games and cards. Now she takes piano lessons and plays tennis. She won the first tournament she played in last month. And she likes to read dumb mystery stories. I like playing baseball, or watching

baseball on TV, or reading and writing about it, and organizing my baseball card collection. I’ve even got some old cards my dad collected when he was a kid.

In the last few months Kendra has also seemed sensitive about being black. During ‘Black History Month’ in school she started reading about famous African-Americans. When we studied slavery and the Civil War in our history class, she got really angry about how the African slaves were treated. She almost cried in class when she presented her report about the Underground Railroad that helped slaves escape.

But she and I still hang out together.

When we’re walking down the hill in the morning and back up in the afternoon we go by her sister’s grave. Her sister died three years ago. She was at a party at another girl’s house and drowned in the swimming pool. Her name was Moniqa and she was six when it happened. Kendra stops by the grave for a minute every morning and every afternoon.

There’s another grave that we look at every day, too. We call it the ‘lonely grave.’ It sits by itself all the way at the lower end of the cemetery, ten yards or so from the other graves and close to a hedge that runs beside the cemetery. It looks pretty old. We’ve never gone over to see who’s buried there, but we always look at it. Sometimes we try to guess why somebody would be buried all alone like that.

Kendra says I ought to write a story about it. But the stories I write always start with something I know, like baseball. How could I write a story about somebody who died—maybe a long time ago—when I don’t know anything about them?

Kendra grabbed my arm. “Steve, look! There are flowers on the lonely grave.