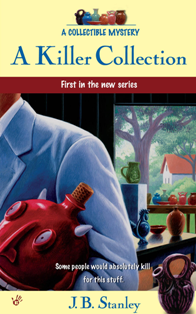

Library

COZY/ANTIQUES/

AMATEUR SLEUTH MYSTERY

AMATEUR SLEUTH MYSTERY

A KILLER COLLECTION

The

potter’s hands were wide with short, thick

fingers, gnarled and cracked from a lifetime of

work. Small burn scars criss-crossed the tough

skin on the palms from feeding wood into the

kiln. Dried clay was wedged beneath the ragged

fingernails. Specks of it dotted the potter’s

apron and stuck like gray flies to his muscular

forearms.

He reached under the cloth and drew out a ball of brown clay, looking it over for any signs of obvious impurities. He placed it on the scale and removed a few chunks from the ball until the scale read five pounds. He lumped the leftovers together and returned them to their shelter to wait under the wet cloth.

Slapping the ball on his wheel so that it would hold fast and create the right amount of suction, he dipped his fingers in a pail of cloudy water and drizzled it over the expectant clay. He began pumping the foot pedal on the wheel and as it spun around, he moistened the clay until it became malleable beneath his hands.

As the potter centered the bulk, it lurched a bit, like a drunk, and then rose upwards like a giraffe craning its neck to reach a higher branch. The wheel hummed softly as the potter worked under the light of a single bulb with the sounds of bluegrass music on the radio.

The clay was alive. Warm below his arms, it moved, stretched, and twisted. He cupped his fingers around its body, forcing the ripples to grow upward in a steady, curving shape. He pressed more firmly at the base, and hips seemed to grow as the weight of the clay settled onto itself. Around the rim, the potter pinched with one hand and smoothed the swelling sides with the other. Then, he let the pace of the wheel slow as he curled his hand around the neck of clay, pushing it upward in a gentle choking motion until it was a symmetrical spout, obedient to his will.

With a knife, he cut off the extra piece of neck and smoothed the insides of the opening. He stepped back and examined the piece, looking at the base, the round sides, and back up to the top where the centered spout emerged in perfect lines.

Satisfied, he slid a piece of wire beneath the jug and moved it gingerly onto a stone slab where it would dry. This one would not get a face. It was too late in the evening and the potter was tired. He had made enough for one day.

As he switched off the radio, he noticed the little lump of leftover clay peeking out from beneath the damp cloth. A new wedge awaited him tomorrow, and he didn’t really want to unwrap the whole thing just to save this small bit. Still, he hated to waste a piece of clay. He paused, picked it up, held it, thinking.

His hands moved over it, hesitating. They weren’t sure what they were supposed to do. Without the wheel, things were uncertain. Pieces could become anything, imperfect, different.

The potter smoothed the lump into a rounded body, then pushed up a thick neck with one hand and widened the head with the other. He pinched out two long, rounded ears, and pulled forward a small nose and cheeks. Dipping his hands into the water, He smoothed the body and pushed out a swollen hump to become the back and the hind leg, then pulled out two, long, identical front legs from the clay below the head. With a wooden carving stick, he traced an upright cottontail on the base of the back leg, drew paws into the little feet, and made a triangular nose, winking eyes, a grinning mouth, and six whiskers. Lastly, he carved his initials and a number onto the base.

The potter smiled, flicking away any flecks of clay from around the last piece of work he would do that night. He hid it far back behind the other taller pieces where it could remain a surprise until the moment was right. The rabbit smiled back at him, sharing his secret among the crocks and churns, the pitchers and bowls, and the face jugs with their rows of crooked teeth. It waited for the time when the potter’s hands would reach out with his brush and glaze its naked body into a cobalt the color of the deep sea. The clay was patient. It had waited hundreds of years to be formed; it could wait a little longer to be burned blue by the kiln fire.

It waited. But the gentle hands of its creator would never come again.

He reached under the cloth and drew out a ball of brown clay, looking it over for any signs of obvious impurities. He placed it on the scale and removed a few chunks from the ball until the scale read five pounds. He lumped the leftovers together and returned them to their shelter to wait under the wet cloth.

Slapping the ball on his wheel so that it would hold fast and create the right amount of suction, he dipped his fingers in a pail of cloudy water and drizzled it over the expectant clay. He began pumping the foot pedal on the wheel and as it spun around, he moistened the clay until it became malleable beneath his hands.

As the potter centered the bulk, it lurched a bit, like a drunk, and then rose upwards like a giraffe craning its neck to reach a higher branch. The wheel hummed softly as the potter worked under the light of a single bulb with the sounds of bluegrass music on the radio.

The clay was alive. Warm below his arms, it moved, stretched, and twisted. He cupped his fingers around its body, forcing the ripples to grow upward in a steady, curving shape. He pressed more firmly at the base, and hips seemed to grow as the weight of the clay settled onto itself. Around the rim, the potter pinched with one hand and smoothed the swelling sides with the other. Then, he let the pace of the wheel slow as he curled his hand around the neck of clay, pushing it upward in a gentle choking motion until it was a symmetrical spout, obedient to his will.

With a knife, he cut off the extra piece of neck and smoothed the insides of the opening. He stepped back and examined the piece, looking at the base, the round sides, and back up to the top where the centered spout emerged in perfect lines.

Satisfied, he slid a piece of wire beneath the jug and moved it gingerly onto a stone slab where it would dry. This one would not get a face. It was too late in the evening and the potter was tired. He had made enough for one day.

As he switched off the radio, he noticed the little lump of leftover clay peeking out from beneath the damp cloth. A new wedge awaited him tomorrow, and he didn’t really want to unwrap the whole thing just to save this small bit. Still, he hated to waste a piece of clay. He paused, picked it up, held it, thinking.

His hands moved over it, hesitating. They weren’t sure what they were supposed to do. Without the wheel, things were uncertain. Pieces could become anything, imperfect, different.

The potter smoothed the lump into a rounded body, then pushed up a thick neck with one hand and widened the head with the other. He pinched out two long, rounded ears, and pulled forward a small nose and cheeks. Dipping his hands into the water, He smoothed the body and pushed out a swollen hump to become the back and the hind leg, then pulled out two, long, identical front legs from the clay below the head. With a wooden carving stick, he traced an upright cottontail on the base of the back leg, drew paws into the little feet, and made a triangular nose, winking eyes, a grinning mouth, and six whiskers. Lastly, he carved his initials and a number onto the base.

The potter smiled, flicking away any flecks of clay from around the last piece of work he would do that night. He hid it far back behind the other taller pieces where it could remain a surprise until the moment was right. The rabbit smiled back at him, sharing his secret among the crocks and churns, the pitchers and bowls, and the face jugs with their rows of crooked teeth. It waited for the time when the potter’s hands would reach out with his brush and glaze its naked body into a cobalt the color of the deep sea. The clay was patient. It had waited hundreds of years to be formed; it could wait a little longer to be burned blue by the kiln fire.

It waited. But the gentle hands of its creator would never come again.